You might have heard the word tossed around in casual conversation but the origins of its meanings go deeper than one might think. Purgatory. Sometimes, it’ll refer to a liminal location in which a character is trapped and must escape and usually, movies about purgatory will produce less-than-friendly dreams after watching for the first time (see Jacob’s Ladder, Silent Hill, The Machinist, and Shutter Island to get a glimpse of what we’re talking about).

Purgatory is typically related to Catholicism, but its origins are much more pagan in nature, as we’ll explain shortly. It began as a state for which souls of neither good nor evil nature could exist; it later expanded into the Catholic church during the Middle Ages and fleshed itself into a more specific location. Curious to learn more? Read below.

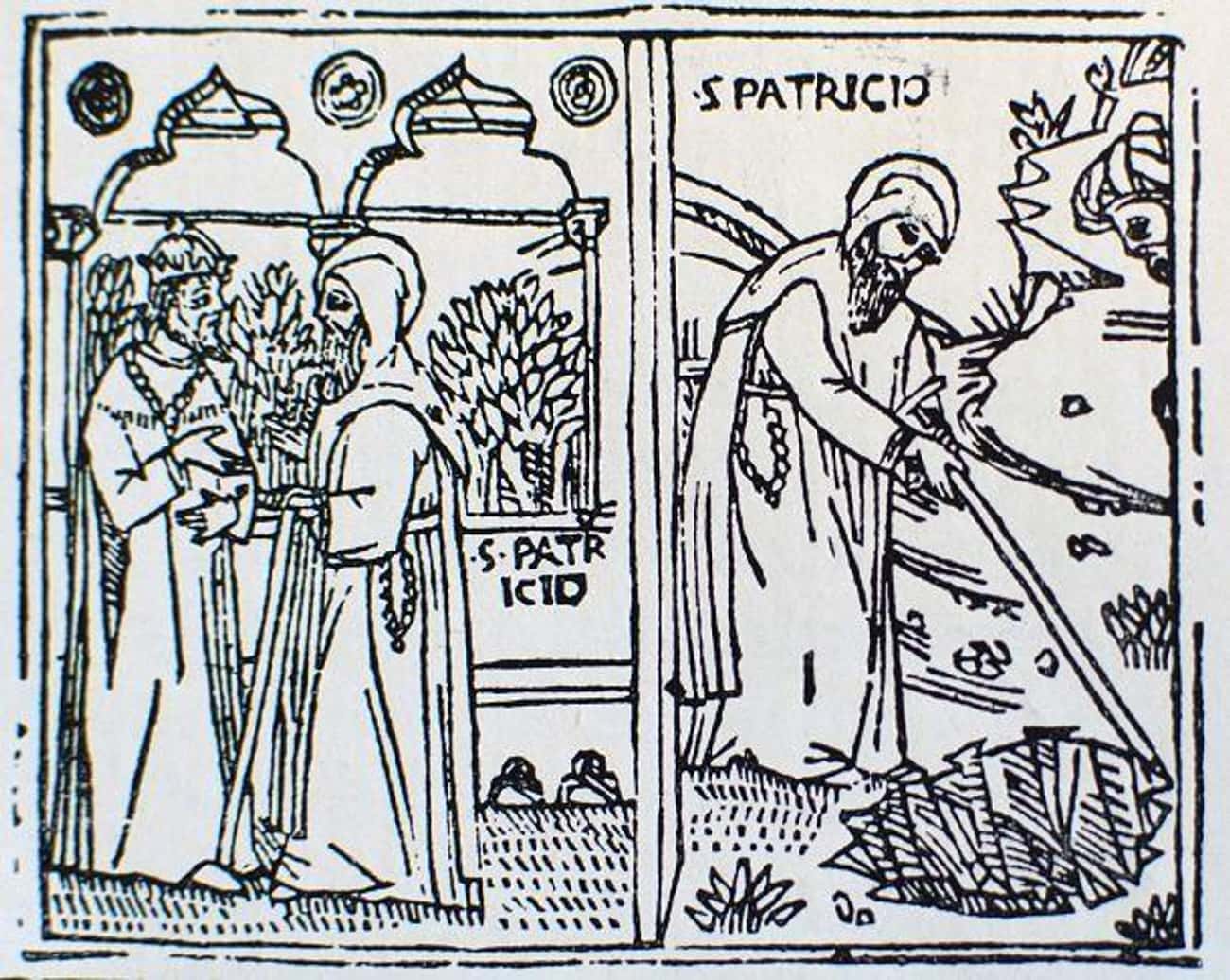

‘Purgatorio’ First Appeared In Writing Within The ‘Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii’

The first use of the term purgatory – or purgatorio – occurred in the Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii, a 12th-century text attributed to H. of Saltrey. The author was most likely a Cistercian monk in Ireland, who recounted a tradition within the Irish church in which an Irish knight, Owein (also Owain, Eoghan, or John) visited St. Patrick’s Purgatory.

Owein was a knight who fought during the 12th century. One day, he was alarmed at his own actions, specifically those committed during the civil war surrounding King Stephen’s reign, and began to fear his eternal fate. As he contemplated his evil deeds, he confessed to the bishop and performed penance as a means of forgiveness and reconciliation. Owein was so contrite that he told the bishop he would travel to St. Patrick’s Purgatory to achieve absolution. The bishop told him that was unnecessary and prescribed fasting and prayer instead.

Owein, determined to go to Purgatory, descended into a dark, gruesome hole with the hopes of seeing Paradise on the other side. For Owein, Purgatory was a means to an end. He persevered through Purgatory with the promise of salvation.

Purgatory Was Shown To Saint Patrick During the Fifth Century CE

According to legend and the Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii, St. Patrick received divine guidance about purgatory from God. Patrick was a Christian missionary who lived at some point during the fifth century and wanted to save the Irish from paganism. However, the Irish would not convert to Christianity unless he proved himself able to cross to the other world and back again.

According to one version of the legend, while Patrick slept one night, or perhaps in a vision, St. Patrick was visited by God who led him to a sparse, barren location. The divine guide showed him a pit and told him that anyone who entered into the place and spent one day and one night there would receive absolution. When St. Patrick awoke, there was a book and a staff before him, left by God as symbols of authenticity.

While the details of the story differ depending on the source, in all tellings, St. Patrick was the recipient of divine knowledge, and it was he who found the entrance to St. Patrick’s Purgatory.

Early Church Fathers Theorized Intermediary States For Souls Neither Good Nor Bad

As a pilgrimage site, St. Patrick’s Purgatory gained increasing importance during the Middle Ages, but the early Church Fathers discussed the idea behind a purgatory-like state previous to the Middle Ages. During late antiquity, St. Augustine of Hippo argued that there are some “who have departed this life, not so bad as to be deemed unworthy of mercy, nor so good as to be entitled to immediate happiness.”

He identified souls that carried over to the afterlife still tainted by sin but worthy of purification, suggesting that there must have, therefore, been an intermediary state where this took place.

A century later, St. Isidore of Seville further justified this idea, using the book of Matthew 12:32, which states that “whosoever shall speak a word against the Son of man, it shall be forgiven him, but he that shall speak against the Holy Ghost, it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, nor in the world to come” to justify the idea that “some sins will be forgiven and purged away by a certain purifying fire” in between this life and the next.

In both instances, the purification of the soul took place after death, but not in a physical location. Purgatory, as it would become known, was for different types of sinners whose souls needed to be saved in order to achieve salvation.

People Were Making Pilgrimages To Saint Patrick’s Purgatory Before The Legend Was Recorded

According to the Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii, Owein’s journey to Purgatory took place around 1150. The text itself was written sometime during the 1180s, but there were references to a pilgrimage site associated with St. Patrick as early as 1120. David, the Irish rector at Wurzburg in Germany, described St. Patrick’s Purgatory in his own works, but these were far less known than those that recounted Owein’s journey and the legend that developed around it.

It is widely believed that St. Patrick’s Purgatory is located on Station Island in Lough Derg, County Donegal. Pilgrims must undergo three days of fasting, sleep deprivation, and exposure to hyperthermia. 15,000 visitors still undergo this difficult religious experience every year.

St. Patrick’s Purgatory’s increasing popularity and presence in Christian literature reflected the growth of the concept of purgatory itself. The contributions of Church Fathers like St. Augustine and the experiences of holy men like St. Patrick synthesized to establish Purgatory as a Roman Catholic truth.

Medieval Purgatory Was A Place Where People Went Through A Purification Period In Order To Go To Heaven

From late Antiquity through the Middle Ages, the religious and cultural development of Purgatory expanded through penitential literature and commentaries on the postmortem purification of the soul. Purgatory was a state in between life and salvation where one’s soul would be purged of sin.

According to historian Jacques Le Goff, purgatory – or the “third place” – emerged as an alternative to dualistic beliefs about Heaven and Earth. Goff explained that in this place, souls “found themselves between the death of the individual and the Last Judgment […] that certain sinners might be saved, most probably by being subjected to a trial of some sort.”

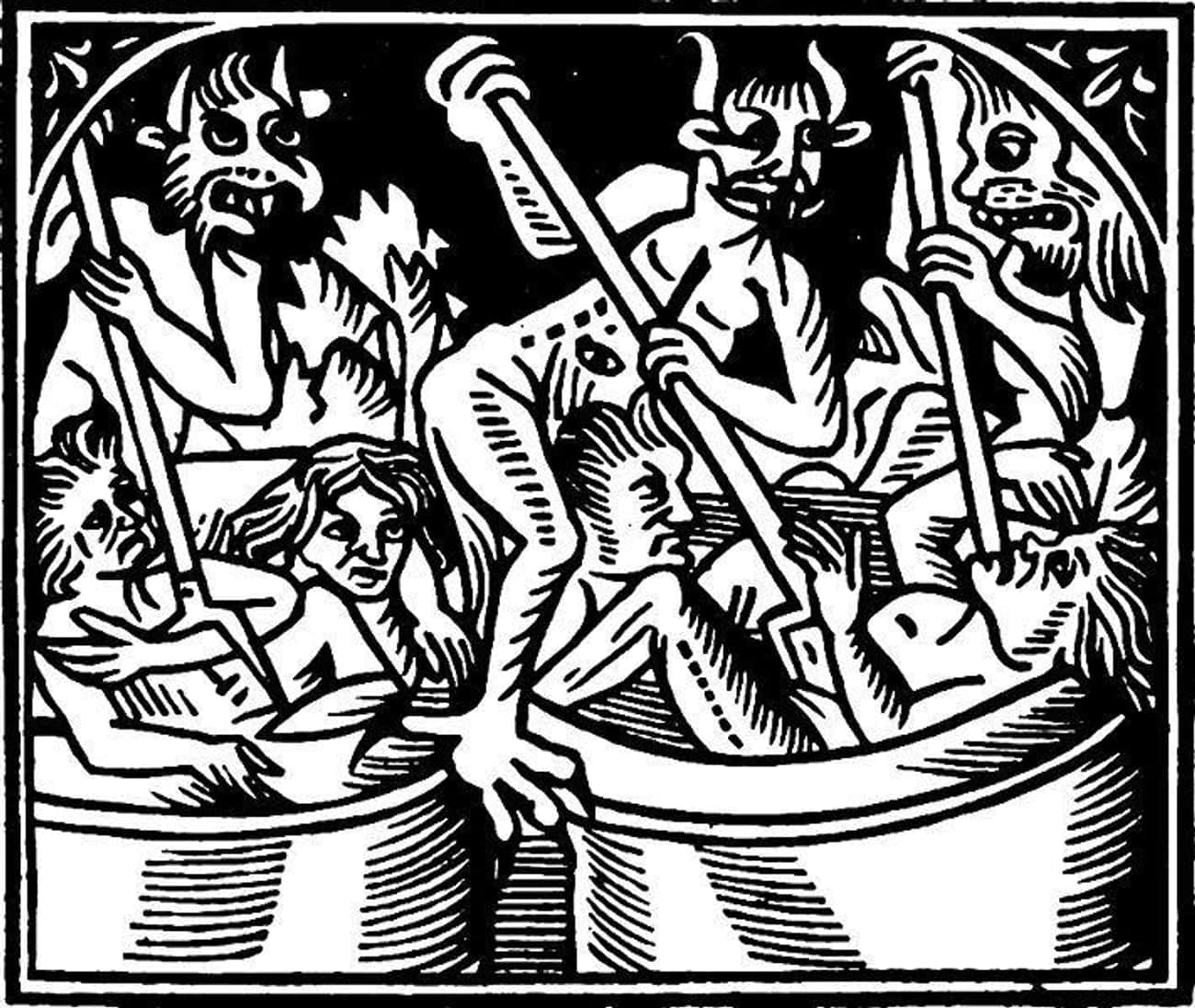

The connections between St. Patrick’s Purgatory and the Christian conception of an intermediate state saw growth through the writings of medieval chroniclers. 12th-century chronicler Gerald of Wales, for example, wrote about St. Patrick’s Purgatory as a place rife with “malignant spirits” where individuals were “crucified all night with such severe torments […] continuously afflicted with many unspeakable punishments of fire and water and other things.” Once an individual underwent this, however, he would “not have to endure the pains of hell – unless he commit some very serious sin.”

As Purgatory became more ingrained in the Christian tradition, the debate transitioned to what Purgatory was like instead of whether or not it existed.

A Person’s Time In Purgatory Could Have Been Shortened Through Prayers, By The Living, Or Indulgences

Prayers for the dead were part of Christian practice, ingrained in the Christian calendar, and intertwined with saints, monastic confraternities, and intercession. Prayers could lessen the time one’s loved one spent in the intermediate space between life and Eternal Paradise. Intercessors – men and women in monastic settings as well as the laity in their daily religious practices – were tasked with assisting the dead in their ascension to Heaven.

This was increasingly a concern as notions of Purgatory took on increasingly horrific imagery. There was no clear indication as to how long one’s soul may be in Purgatory and the amount of prayer needed was difficult to assess, so additional methods to lessen one’s time developed.

Another way to lessen time in Purgatory was through indulgences. Several types of indulgences began in the early 11th century as a means of remitting the guilt of sin. Partial indulgences remitted temporal punishments but did not cleanse the soul entirely. Sometimes indulgences took the form of prayer, but they soon became associated with monetary gifts given to the Church as well.

Plenary indulgences involved a complete remission of sin. Pope Urban II offered a plenary, or full, indulgence to Crusaders when he announced the First Crusade in 1095:

God has conferred upon you above all nations great glory in arms. Accordingly undertake this journey for the remission of your sins, with the assurance of the imperishable glory of the kingdom of heaven.

Indulgences were also offered in celebration of jubilee years, something Pope Boniface VIII granted in 1300. As the 14th century progressed, indulgences became increasingly connected to money. In 1344, for example, Pope Clement VI awarded 200 plenary indulgences to Catholics in England alone.

The Eastern Orthodox Church Questioned The Concept Of A Temporary, Cleansing Space For The Soul

When the Western and Eastern Catholic churches formally split in 1054, there were numerous doctrinal divides that contributed to the division. The Eastern Orthodox Church had theology based in Greek language and philosophy, while the Roman Catholic Church was steeped in Roman law and Latin. Issues over clerical celibacy, the language in the Nicene Creed, leavened bread, and the rights of bishops all contributed to tensions between the two groups. When they finally separated, the East distinguished itself by not adopting the doctrine of Purgatory.

Eastern Orthodoxy struggled to understand the vagueness of the doctrine of Purgatory and wanted to define its location and physical attributes. Most importantly, the idea of fire and Purgatory gave Eastern Orthodox Christians pause. From the perspective of the West, there was a limited time during which sinners would experience fire as a form of purification. In the East, this went against the Lord’s mandate since there was supposed to be eternal fire for individuals who deserved it.

In short, the East challenged the West’s way out of punishment and would not relent.

Purgatory Solidified In The Catholic Doctrine During The 12th And 13th Centuries

Granting indulgences was a right of the clergy, most importantly the pope. Bishops and archbishops could grant indulgences, although abuse resulted in limitations by the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215:

Since, through indiscreet and superfluous indulgences which some prelates of churches do not hesitate to grant, contempt is brought on the keys of the Church, and the penitential discipline is weakened, we decree that on the occasion of the dedication of a church an indulgence of not more than one year be granted, whether it be dedicated by one bishop only or by many, and on the anniversary of the dedication the remission granted for penances enjoined is not to exceed forty days. We command also that in each case this number of days be made the rule in issuing letters of indulgences which are granted from time to time, since the Roman pontiff who possesses the plenitude of power customarily observes this rule in such matters.

When the Eastern and Western church split, the doctrine of Purgatory became even more ingrained in Roman Catholic doctrine. Between the schism in 1054 and Pope Innocent IV’s letter in 1245, attempts to reunite the churches were unsuccessful. As a condition of reunification during the 13th century, Pope Innocent IV desired that members of the Eastern Church acknowledge the “place of purgation […] according to the traditions and authority of the Holy Fathers, this name is Purgatory.” Not only did he define Purgatory formally, but he made it conditional for uniting the Church.

Disagreement Between East And West Helped Refine Purgatory In The West

After Pope Innocent IV clarified what Purgatory was and how it functioned within the Roman Catholic Church, scholars and clergymen continued to expand upon the concept. At the Second Council of Lyons in 1274, representatives from the Eastern and Western church met to try to negotiate their differences. Purgatory received a specific conciliar endorsement, an important validation of its place in doctrine.

Within the Profession of Faith put forth by Michael Palaeologus, the Byzantine Emperor who assured his Western counterparts reconciliation was possible, it stated:

Because if they die truly repentant in charity before they have made satisfaction by worthy fruits of penance for (sins) committed and omitted, their souls are cleansed after death by purgatorical or purifying punishments […] and to relieve punishments of this kind, the offerings of the living faithful are of advantage to these, namely, the sacrifices of Masses, prayers, alms, and other duties of piety.

The Profession of Faith was approved but later rejected by the larger community of Greek clergymen and remained a point of contention as the two sides continued to discuss the issue through the 15th century.

Medieval Literature And Art Perpetuated Catholic Ideas About Purgatory

With increasingly articulate and specific visual and written accounts of Purgatory, the transition from a mere concept to actual place was more or less complete by the 13th century. Fear of death, an unknown amount of time in Purgatory, and the pain one’s soul would endure in manuscripts, paintings, and other works of art showed how horrible a “bad death” – one for which an individual was unprepared – could be.

During the later Middle Ages, sermons by the likes of Jean Tisserand described the fire of Purgatory as all-consuming and cleansing, reminding listeners that “after the Judgement the fire will descend with the damned into hell.” Tisserand encouraged his flock to do what was necessary while on Earth to lessen time in Purgatory for fear of failing to escape.

Poets, minstrels, and writers pushed the notion of Purgatory further, reciting verses about smouldering fires and cries of pain. There was some hope, however. It was widely believed that if one had done his duty, he could “not be prevented from going straight to Paradise.”

Mendicants And Growth Of Universities Perpetuated The Concept Of Purgatory

According to Jacques Le Goff, the noun “purgatory” was not in wide usage until the late 12th century, when it was popularized by the theologians in the universities in Paris. Theologians at the University of Paris, many of whom were Franciscan or Dominican friars, debated questions about Purgatory and the benefit it offered to one’s soul.

One noteworthy contributor to the conversation was St. Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican friar, who died on the eve of the Second Council of Lyons in 1274. Aquinas wrote extensively about Purgatory, offering the assertion:

There is a Purgatory after this life. For if the debt of punishment is not paid in full after the stain of sin has been washed away by contrition, nor again are venial sins always removed when mortal sins are remitted, and if justice demands that sin be set in order by due punishment, it follows that one who after contrition for his fault and after being absolved, dies before making due satisfaction, is punished after this life. Wherefore those who deny Purgatory speak against the justice of God: for which reason such a statement is erroneous and contrary to faith.

Dante Articulated Levels Of Purgatory That Helped Define It As A Physical Location

When Dante Alighieri wrote his Divine Comedy during the 15th century, he presented a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise in narrative form. His detail, imagery, and vision reflected the medieval worldview and contributed to perceptions of the afterlife. The second part of the Divine Comedy, Purgatorio, contained seven levels, each of which corresponded to one of the seven deadly sins.

Presented as a terraced mountain on an island, Dante’s presentation of Purgatory was somewhat hopeful. His work, and others’, solidified the notion that Purgatory was a physical place, not simply a theological ether where one’s soul remained for an undetermined amount of time.

Some Criticism Of The Church Led To A Reaffirmation Of Purgatory During The Council Of Trent

Photo: Anonymous / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

When the Catholic Church called the Council of Trent during the mid-16th century, it was in response to criticisms hurled at them by Protestant challengers. As part of the Counter-Reformation, the Council of Trent was held between 1545 and 1563, during which it implemented a series of reforms and reaffirmed numerous doctrines.

One of the major criticisms of the time was the excess and wealth of the Church, which the practice of indulgences highlighted. In 1517, Martin Luther famously challenged the Church’s practice of selling indulgences to remit sin and lessen one’s time in Purgatory. At the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church issued a decree urging moderation, acknowledging abuses, and admonishing clergymen that took part in “criminal gain.” The degree also tasked bishops with rooting out abuse and corruption “so that the benefit of indulgences may be bestowed on all the faithful by means at once pious, holy, and free from corruption.”

Furthermore, the Council asserted the existence of Purgatory:

[T]here is a purgatory, and […] the souls therein are helped by the suffrages of the faithful, but principally by the acceptable Sacrifice of the Altar; the Holy Synod enjoins on the Bishops that they diligently endeavor to have the sound doctrine of the Fathers in Councils regarding purgatory everywhere taught and preached, held and believed by the faithful.