Many people today have misconceptions about the ancient world, even if they might not realize it. Our historical knowledge is often a just mixture of misinformation, half-truths, and the last historical movie we saw. This happens for many reasons. Information has a way of getting distorted as centuries pass, so the further back one goes in history, the less reliable the records. Worse, most of those “records” were actually written by “historians” who were highly biased individuals with an agenda to support a specific person. Finally, in more modern times, pop culture has entered the picture. And you don’t need us to tell you that “historical” movies and TV shows are rarely accurate.

Everyone’s knowledge of history is full of gaps and misconceptions, and it can take a lifetime to unlearn myths about ancient Egypt, ancient Rome, and beyond. To get started on that journey, here are some common misconceptions even history buffs believe.

1. Lie: Celts Were A Thing

Today, many people from the United Kingdom, as well as people with UK ancestry, identify with “Celtic” culture, a distinct group that supposedly flourished in the Bronze and early Iron Ages, occupying much of northern Europe and the modern UK. Eventually, the Celtic culture evolved into many of the modern cultures we know today.

But in reality, there was no single distinct Celtic identity, and there’s no Celtic DNA found in anyone today. And the Celts didn’t call themselves “Celts.” The word “Celt” was first used by the Greeks and Romans, who used it the same way they used “barbarian,” meaning, anyone who spoke a different language.

While many of the tribes the Greeks and Romans considered barbarians did share similar languages, religions, and customs, they weren’t a monolithic group with a unifying identity. The modern idea of a Celtic identity originated in England in the 17th century.

2. Lie: Spartans Were Super Soldiers

In Western culture, the Spartan military is often held up as one of the world’s first elite fighting forces. Part of this concept involves the Spartan military school called the agoge. In the film 300, it’s presented as an incredibly harsh military academy that puts recruits in danger as a way to toughen them up for wars. In reality, the agoge was more like a system of forced indoctrination designed to mold children into soldiers, many of whom didn’t survive the harsh training methods. Part of this training involved stalking and slaying unarmed helots, a subclass of Spartans who were somewhere between serfs and slaves. (In 300, Leonidas hunts a wolf instead.) All manner of abuse and violence were inflicted on Spartan children in the agoge, who would then inflict it on the next group of kids.

But did that dehumanizing environment produce the Mediterranean’s best infantry? While the Spartans may have had minor advantages in tactics and equipment over their rival city-states, those weren’t enough to earn them the title of the best warriors of all time. Although their reputation has them never losing in battles, their real win-loss record was about 50/50. Leonidas’s bravado notwithstanding, Spartans also sometimes surrendered – just as they did at the Battle of Sphacteria in the Peloponnesian War.

3. Lie: The Burning Of The Library Of Alexandria Caused The Loss Of Incalculable Ancient Knowledge

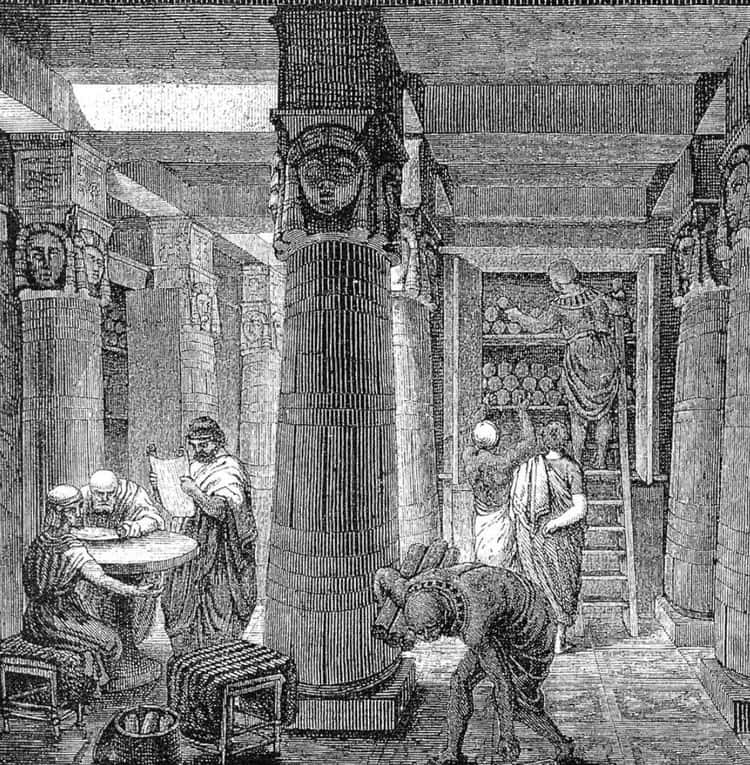

When Alexander the Great built the city of Alexandria on the coast of Egypt, he aimed to make it the most state-of-the-art city in the known world. One of his projects was to build the world’s most comprehensive library – a repository of all the world’s knowledge to that point. The story goes that a few centuries later, when Julius Caesar conquered Ptolemaic Egypt, he also ordered the burning of the library. Because relatively few ancient works of literature have survived to the present, recent historians have considered the library’s destruction one of the greatest losses of knowledge the world has ever known. (This narrative also sometimes gets conflated with events surrounding the demise of Hypatia in the fifth century AD, adding to the confusion.)

But that’s overstating the situation by a lot. The library wasn’t a place where one-of-a-kind ancient manuscripts were stored, containing arcane knowledge that could have changed the course of history. It mostly contained copies of books that could be found in other libraries throughout the Mediterranean. Many of those libraries were also destroyed throughout history, but ancient books still survived. Then as now, those books that appealed to the most people were likely to be the most copied.

The biggest reason why some ancient works of literature were lost is simply that they were written on papyrus. Additionally, when the bound book (or codex) became the preferred method of storing literature in late antiquity, any works that didn’t make the cut to be transcribed into the new format were much likelier to be lost over the centuries.

4. Lie: The Greco-Persian Wars Were A Big Deal

To the Greeks, the Greco-Persian wars were some of the defining events of their times, especially for Athens. When Persia’s Darius the Great arrived in the Aegean in 492 BC with a massive army and plans to invade, it was only Athens and a few other city-states that opposed them. So when the Athenians dealt the Persians a surprise defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, it established the Athenians’ self-image for generations. Marathon meant that the Greeks were strong and brave while the Persians were weak and soft. The enormous influence of Herodotus’s historical writing has only solidified this narrative over the millennia.

But to the Persians, the incident was a minor defeat on the edge of their massive empire. The Persian historical record barely mentions the loss at Marathon. It does hype Xerxes’s later victory at the Battle of Thermopylae and the subsequent punishments the Persians inflicted on the Greeks. Public relations isn’t a new concept.

5. Lie: Ancient Romans Routinely Binged And Purged At Feasts

There are many stories of decadence and excess among the Roman elites, and few of them can be trusted as 100% accurate. One popular misconception is that wealthy Roman citizens had special rooms in their homes just for vomiting. Romans would overindulge at meals, then retreat to the vomitorium to make more room.

But this is a modern idea. The Romans did have a structure that’s now called the vomitorium. It wasn’t a location where people vomited, but rather a passageway built under stadium seats that allowed large crowds to quickly exit. But the Romans themselves didn’t call them that. One Roman writer referred to it that way figuratively, and the nickname stuck.

The idea of a special vomiting room probably originated in the late 19th or early 20th century from someone who misunderstood the word “vomitorium.”

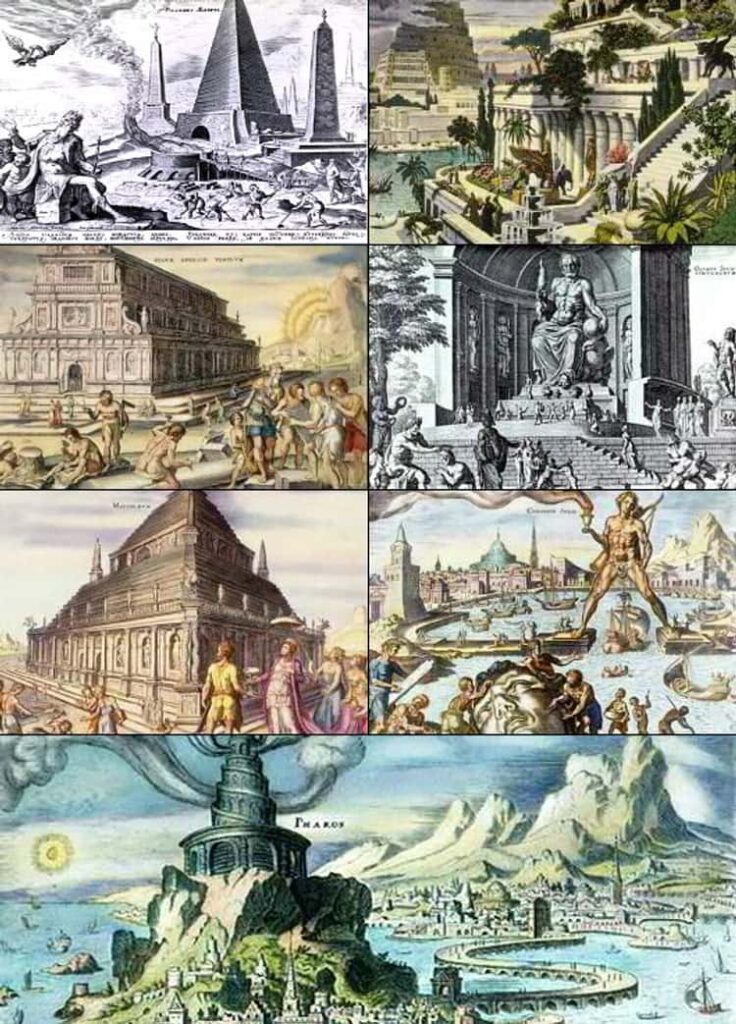

6. Lie: There Were Exactly Seven Wonders Of The Ancient World

Today, the most widely known version of the “Seven Wonders of the World” includes these seven monuments: the pyramids at Giza, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, and the golden statue of Zeus at Olympia.

But ancient people wouldn’t have agreed with everything on that list. The first person known to have listed the seven greatest works of architecture of their time was Antipater of Sidon, who wrote a poem listing the seven wonders in the first or second century BC. Antipater’s version swapped out the Lighthouse of Alexandria for Babylon’s city walls. Other authors in the late-Roman and early medieval period had different lists that included other wonders, like Noah’s Ark, the Temple of Solomon, or Hadrian’s temple at Cyzicus. The Lighthouse of Alexandria only began showing up on lists in the fifth and sixth centuries AD, hundreds of years after people started listing wonders.

The reason these lists changed so much is likely because many of the landmarks on Antipater’s original list had fallen into ruin, forcing later historians to repopulate the list with more current landmarks. Of course, nowadays, only one wonder – the oldest of them all – still survives.

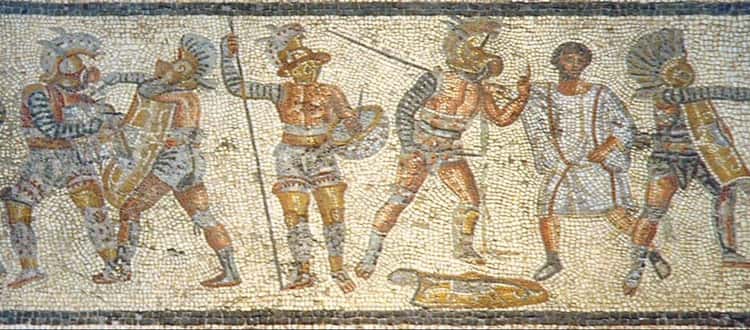

7. Lie: Gladiators Fought To The Death

No doubt movies like Gladiator are responsible for this misconception about the Roman gladiator system, which is that gladiator matches were meant to be fights to the death, every time. Gladiators did occasionally fight to the bitter end on purpose, but this was rare. For their owners and trainers, It was much more business-savvy to keep gladiators alive.

Most gladiators were slaves, and the costs to acquire and train them were high. To then throw a gladiator’s life away would have left many gladiators’ owners bankrupt. Since most Roman audiences were happy with a bloody fight that resulted in a clear winner, but not necessarily a fatality, trainers had an incentive to treat their gladiators relatively well. Gladiators may have received medical treatment, and some became famous enough in the arena to purchase their freedom. Archaeological evidence suggests that some gladiators were intentionally fattened up so that their bodies would have an extra layer of subcutaneous fat, allowing for more flesh wounds.

It was still a brutal life, and many gladiators did perish in their line of work. But most fatalities were unintended.

8. Lie: The Roman Senate Was Like The US Senate

They might share a name, but the ancient Roman and modern US senates hardly resemble each other. There’s also the issue of which Roman senate to compare the US Senate to. According to legend, the Roman Senate was formed right after Romulus drove out the last Etruscan king. It would last through the republic and imperial periods until the end of the empire. Its role in government would change significantly in different periods. But since the Roman Republic (509-27 BC) was the time when the Roman Senate had the most influence, it’s the most comparable.

The biggest differences between the senate of the Roman Republic and today’s US Senate are that the Roman Senate was designed to be class-based, and Roman senators weren’t elected. While US senators are elected by citizens (or, originally, by elected state legislatures), Roman senators were appointed from the patrician class – the oldest and wealthiest. The plebeians had their own legislative assembly, the Plebeian Council, but it had no authority over the Senate or patrician affairs.

Also, unlike the US Senate, the Roman Senate didn’t pass laws. Instead, the Roman Senate offered Senatus consultum, or non-legally binding opinions on policy. The Roman Republic still usually followed them, however.

9. Lie: Athenian Democracy Was Democratic

In modern countries that govern by democracy, many people point to ancient Athens as the inspiration for this system. We still honor the Athenians for inventing the world’s first democracy, which lasted from 508 to 322 BC, a period of 186 years, but it’s a good thing modern countries didn’t literally model their governments on a sixth-century BC Greek city-state. If they did, inequality would be an even greater problem than it already is.

The Athenian democracy was considered a government “of the people” – just not all of them. The main governing body was the Assembly of Citizens, where all citizens could meet to debate that day’s agenda and vote on legislation. It was the unusual ancient government system that allowed lower-class citizens to have a political voice. But otherwise, “of the people” excluded women, slaves (which themselves constituted up to a third of the total population), and citizens whose parents weren’t Athenian.